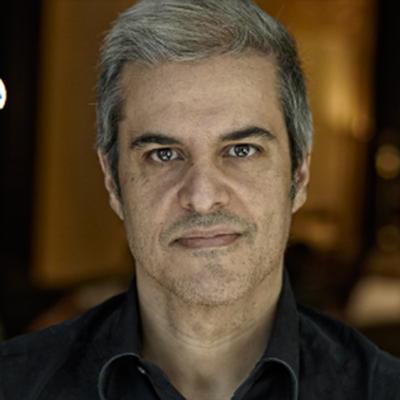

With the killing of Bin Laden in Abbottabad, al-Qaeda is as good as dead. This was never a mass movement, or one with connections to real-world struggles like the Arab spring — it fed off the fantasies of loners and theatrical mise en scène. The analysis by Olivier Roy.

Osama Bin Laden was already dead before the Americans attacked his compound in Abbottabad – politically, at least. The political death of al-Qaeda occurred on 17 December 2010 at Sidi Bouzid in Tunisia when the street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi set himself alight. Bouazizi’s suicide, whatever its personal motivation, was a political event, but this suicide had nothing to do with terrorism, the rejection of America, the struggle against Zionism or the creation of a global caliphate.

The great wave of democratic revolts in the Arab world has shown the extent to which al-Qaeda had already been marginalised, as much organisationally as in the form of a political discourse. Al-Qaeda, which has never had roots in social movements, ceases to exist if it isn’t on the front pages and on our television screens.

In fact, the marginalisation of al-Qaeda corresponds, as I have noted in previous articles in the New Statesman, to a paradigm shift in the Arab world that is religious as well as political. The demand for freedom and democracy in a national context has displaced the imaginary umma, the world community of Muslims, in its struggle with the west. Charismatic authoritarian personalities such as Bin Laden no longer exert any fascination on an individualistic and rather pragmatic younger generation.

However, the coincidence of Bin Laden’s physical and political deaths is too remarkable not to raise a number of important questions. The first, naturally, concerns Pakistan. It is impossible that the Pakistani Directorate of Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) did not know where Bin Laden was – for some, if not all, of the time. And it is simply implausible that it was kept entirely in the dark about the US operation in Abbottabad. Pakistan previously protected Bin Laden and then recently decided to cut him loose. Why? First, he was no longer a political force in the Muslim world. He had become a burden rather than an asset. Second, the Taliban in Afghanistan and Pakistan had cut their ties with Bin Laden, not for political reasons but because Bin Laden no longer had anything to offer them – not money, not volunteers, not strategy. It is telling that Bin Laden had sought refuge in an area outside the Taliban’s sphere of influence, whereas many observers (myself included) thought that he was either in the tribal regions or in Karachi, both Pashtun and Taliban strongholds.

At a stroke, the death of Bin Laden opens up perspectives on the conflict in Afghanistan. The principal war aim of western forces when they invaded Afghanistan in October 2001 was the destruction of al-Qaeda and the death or capture of its leader. That goal has now been achieved. So why stay there? Even if western governments tried to persuade public opinion that there was a much broader justification for the invasion (saving Afghan women from the misogynistic dictatorship of the Taliban), no one today is ready to fight to ensure that sharia law and the mandatory wearing of the burqa are not imposed in Kabul.

In fact, it is now hard to justify the western presence in Kabul. But it is possible for Nato to leave with its head held high, claiming that its mission has been accomplished. And that is precisely what both the Pakistani establishment and public opinion want – which explains why Bin Laden was cut loose: not only did he no longer serve a purpose alive, but his death would perhaps allow the Pakistanis to become the masters in Afghanistan.

Islamabad has been constant in its aims in Afghanistan since at least as far back as the Soviet invasion of 1979: it wants a friendly power in Kabul, and has concluded that only an Islamic, Pashtun regime can ensure that. The ethnic connection with Pakistani Pashtuns, who exert considerable influence in the ISI and the Pakistani army, is viewed as an asset. Other ethnic groups, especially Persian speakers, are regarded – mostly without foundation – as potential agents of Iran. In Islamabad’s eyes, the Islamic influence also serves as a bulwark against an Afghan nationalism that could push Kabul into an alliance with India (this, in fact, is already happening with Hamid Karzai’s regime). Until 1993, this Pashtun fundamentalist strategy centred on Gulbuddin Hekmatyar’s Hezb-e-Islami. Since 1994, it has been focused on the Taliban. (The radicalisation of Pakistani Pashtuns along the same lines has not caused Islamabad to withdraw its support for the Taliban in Afghanistan.)

Officially, the policy of exerting indirect control over Afghanistan has been justified by citing the supposed threat from India. Now, one could criticise the Pakistani obsession with achieving such strategic reach on the grounds that conquering Pakistan is the last thing the Indians want to do. It should be recognised, however, that the civil and the military elite in Pakistan have been unwavering in their wish to place Afghanistan under a kind of protectorate. The Pakistanis want Nato to leave and the death of Bin Laden offers the prospect of an honourable exit. As for the Taliban, they no longer have to choose and explicitly renounce their association with al-Qaeda; they can present themselves as national actors rather than

be seen as international jihadists. Nevertheless, we should not expect the western departure from Afghanistan to be announced any time soon. All that has happened is that an obstacle has been removed, making it conceivable that negotiations could be opened with the Taliban without Nato losing face, and in a context in which the Taliban are no longer associated with the ghost of Bin Laden.

However, Bin Laden’s death will have an impact well beyond the Afghan-Pakistani theatre of operations. What will become of al-Qaeda? Where will those who might once have joined it go? There will be attacks made in al-Qaeda’s name, just as there are attacks made in the name of the “Real IRA” in Northern Ireland. There will be a campaign to prove that Bin Laden is still alive, and there will be new leaders claiming to be his successor. But we should reject the theory that the death of Bin Laden changes nothing as far as the root causes of terrorism are concerned and that al-Qaeda will continue to recruit and to function without him.

I find it difficult to separate Bin Laden from al-Qaeda. In the first place, he was the inventor of the original concept: a network of subcontractors and franchisees using the “Qaeda” label; a flexible organisation, comprising no more than three levels (the centre, the local boss and the group of militants), in which considerable responsibility is given to the “head of operations” charged with carrying out an attack. Al-Qaeda was never a revolutionary party in the Leninist mould, surrounded by satellite organisations and seeking to embed itself among the “masses”. It has always practised the propaganda of the deed, and the charismatic figure of Bin Laden was central to this strategy. Tubby and myopic Ayman al-Zawahiri, Bin Laden’s so-called number two, does not have quite the right image.

Yet much more important is the question of the causes of radicalisation. For a long time it was thought that recruitment to al-Qaeda expressed the resentment of the Muslim world in general, and the Arab world in particular, at the west’s support for Israel and at western intervention in Arab lands. The idea was that so long as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict remained unresolved, the fascination with al-Qaeda would persist, even if the methods it adopted were rejected by most Muslims.

But two factors suffice to show the extent to which al-Qaeda’s appeal was entirely unconnected to strategic issues in the Middle East. First, most of its recruits came from the periphery of the Arab world: second-generation Muslims in Europe, immigrants from East Africa in the UK and émigré Jamaicans and Martiniquans (in the United States, Britain and France); to whom should be added converts of all origins (Christians such as Muriel Degauque, Hindus such as Dhiren Barot and Jews such as Adam Gadahn). There were very few Palestinians in al-Qaeda. Second, as we have seen, the new political movements in the Middle East have developed independently of al-Qaeda. It has never been able to assert itself as a political force in the Middle East. In Iraq, Lebanon, Palestine, Algeria and Morocco, militants close to al-Qaeda have, thanks to their attacks, had a nuisance value at best.

The al-Qaeda old guard (Zawahiri and Bin Laden) were exceptions; none of the recruits who joined the organisation from the 1990s onwards ever campaigned for any political cause in the Middle East. None of them was radicalised in the course of participating in a political struggle (support for the Palestinians, say, or Muslim community action in Europe). Rather, al-Qaeda’s attraction lies in the heroic “narrative”: in carrying out an attack, an isolated individual (often in conflict with his surroundings) avenges the suffering of the virtual global umma. Al-Qaeda always needs a mise-en-scène – the volunteer for death filming himself before carrying out an action, the execution of hostages in front of the camera in a macabre ritual (borrowed, as it happens, from the Italian Red Brigades’ 1978 assassination of the politician Aldo Moro, and proof that the political genealogy of al-Qaeda owes more to the western ultra left than it does to the history of the Muslim world). The staging is then taken up, for free, by the media: rolling coverage of the attack on the World Trade Center, front pages for any attack in which innocent westerners are killed.

This mirror effect exacerbates public fear and gives an apocalyptic global dimension to al-Qaeda action. Bin Laden’s “victory” was to have occupied the space of the media and to have forced the west into putting its fears at the centre of it and then “overreacting”. The media circus we have witnessed since his death was announced was merely the act of a great actor who died on stage playing his final role.

There is a romantic dimension to the Bin Laden persona that fascinates young rebels in search of a cause. The way he presented himself and the cult of heroism and death he cultivated were not the icy calculations of a political militant seeking to achieve a strategic objective. Terrorism here is not a means; it is an end in itself.

The “Arab masses” understood very quickly that Bin Laden was not interested in their cause. He was interested in the cause – his own. There is an element of morbid and narcissistic elitism in al-Qaeda’s terrorism which explains both its appeal for the ardent young and its political failure. This romantic dimension was intimately related to the charismatic person of Bin Laden, and to him alone.

Certainly his ghost will continue to fascinate, attacks will be carried out and his fans will try to keep the flame alive. But the new actors will be mumbling their lines in front of an audience that has become weary and indifferent. Apocalyptic tragedy will be relegated to the news in brief. Even if, as we know, the news in brief is sometimes deadly.

Source: New Statesman